Answering the important questions

Here in the MaPLE lab, we treat the techniques students cultivate in their programming systems classes as general methods for answering a broad range of research questions that arise in and around software when it is used in nontraditional ways. As a result, students without formal training in the techniques we use often ask: "What is PL?," whereas those with training often ask: "How is what you do PL?"

What is PL?

Everyone in PL eventually has the experience of telling someone their research area is programming languages and having that person respond with "Oh? What programming language do you study?" This is understandable; many students' first exposure to PL is still via a programming paradigms course, which have highly variable content. However, the main gist is that there are a variety of ways we can design what a language looks like (i.e., its primitive components and the rules for combining them, or its syntax) and these design choices are supposed to make some things easier than others. Some of the features we believe to be impacted by design are obvious, like usability (e.g., the heated debate about parentheses of Lisp vs. spaces of Python) and some are less obvious, like performance and correctness. Most of these benefits are not just about the language's syntax, but also include reasoning about its semantics, or how we should interpret what the program means or does.

However, quite a bit of PL research these days it not about general-purpose programming languages at all! I'll get more into this in the section below, but for now it can be helpful to just think about PL more abstractly. One of the best high-level views of PL I've seen is Eelco Visser's PLMW 2019 talk, wherein he described PL as being about "getting stuff for free." One mechanism for "getting stuff for free" is designing domain-specific languages (i.e., DSLs, languages designed for a limited and highly specialized domain, not necessarily for human end-users) such that we can say meaningful things about them without actually running them, using existing tools and techniques.

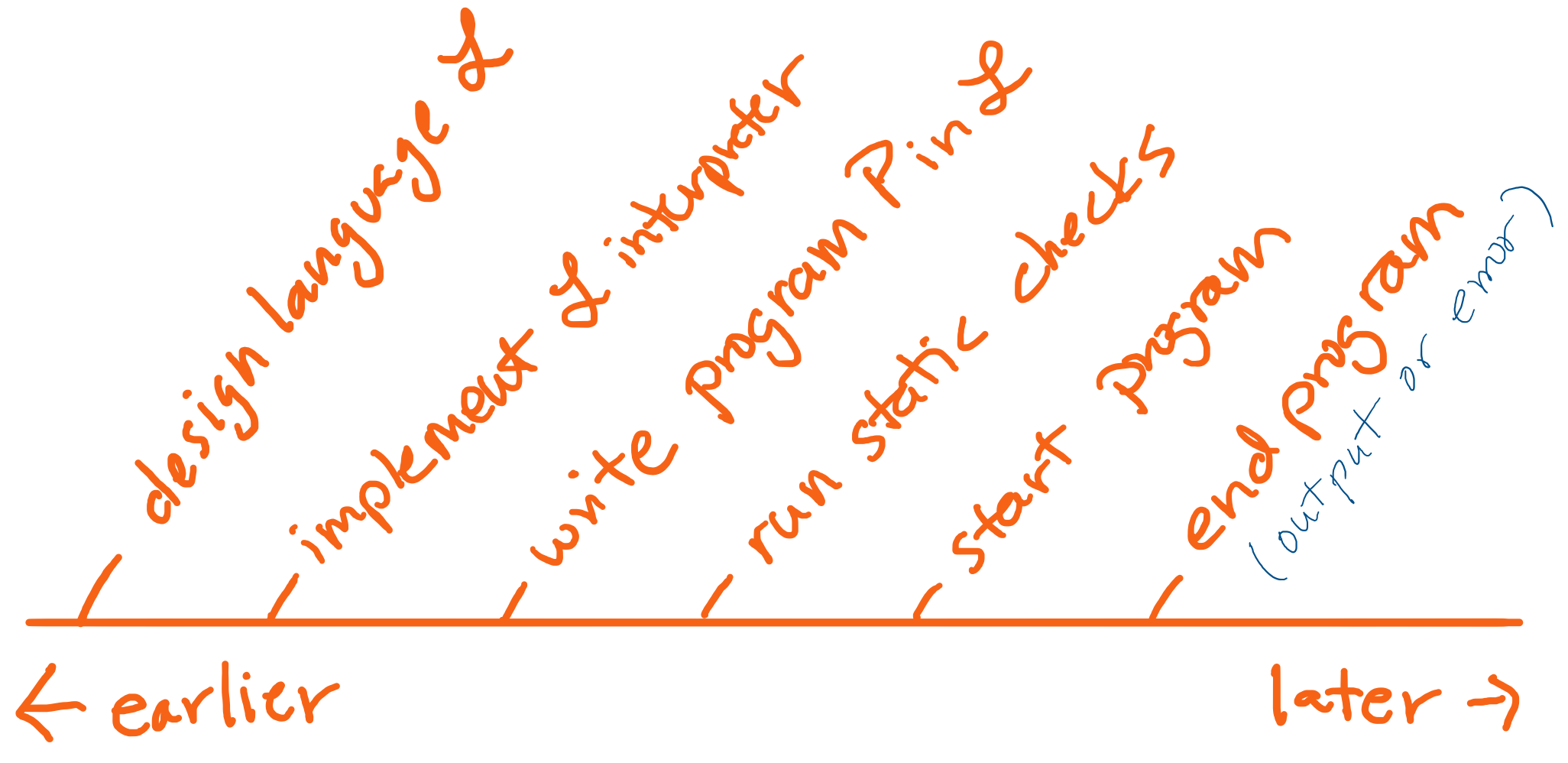

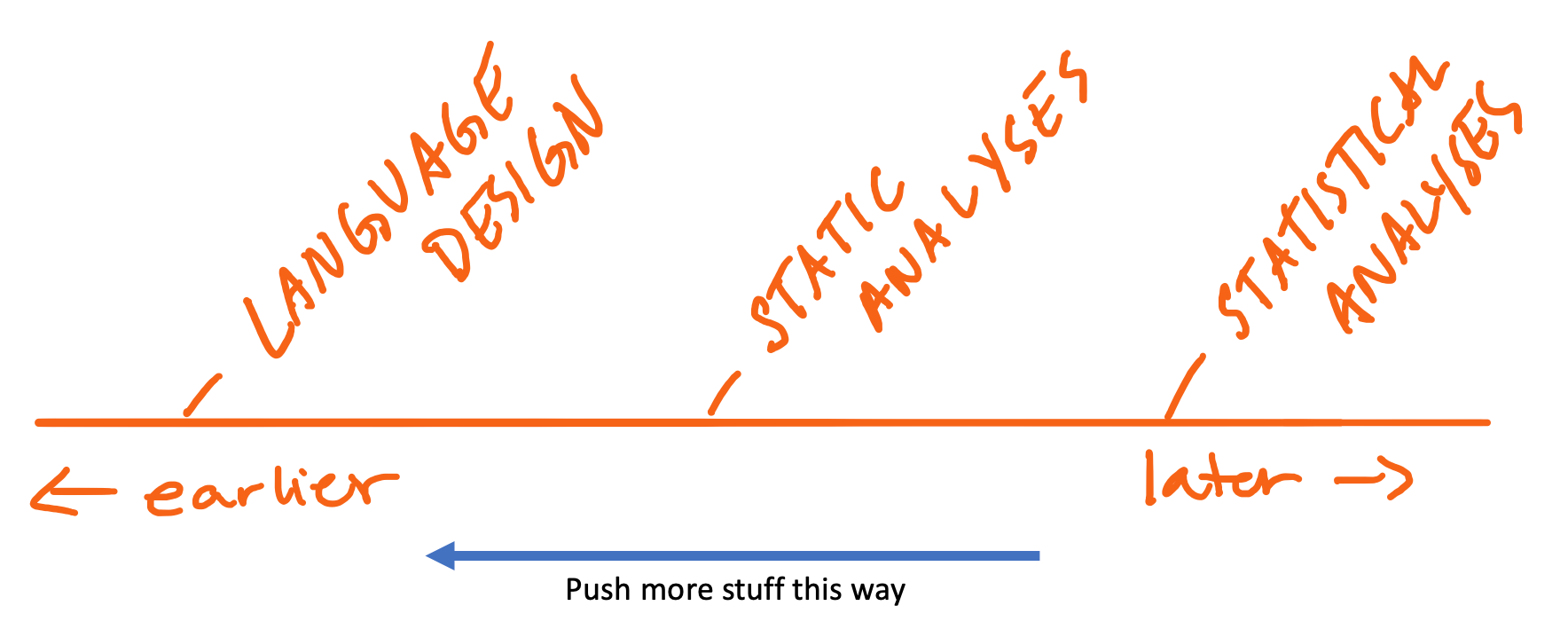

When we analyze programs without actually running them, this is called static analysis. Intuitively, if you can ask important questions about the range of a program's behaviors before running it, you have higher confidence that fewer bad things will happen. Terms like "important questions" and "bad things" are purposefully vague because they depend on the particular domain you are working in. The more we can cleverly encode information in a language's syntax, the easier it becomes to analyze programs statically. One popular goal in PL research is to find ways to catch problems early.

One common point of confusion for newcomers who have a background in computer science but not PL: we know that answering arbitrary questions about the execution of an arbitrary program is undecidable. In PL, we are typically interested in specific questions about arbitrary programs written in a specific language.

How is what you do PL?

PL as a field has become increasingly interdisciplinary, as researchers apply PL concepts to problems not ordinarily thought of as within scope. Much of the work we do in MaPLE is deeply interdisciplinary, reflecting this reality. One perspective on the evolution of PL that I like is the treatment of languages as part of a programmer's broader toolkit, exemplified in this 2018 CACM article. They mention two affordances of this perspective on PL that I like:

- Enable creators of a language to enforce its invariants, and

- Turn extra-linguistic mechanisms into linguistic constructs.

We enforce invariants through language design choices, such as prohibiting certain operations (e.g., recursion), making certain constructs atomic (e.g., parallel operators), and equipping programs with complementary systems that encode "extra" information beyond what's necessary to execute the program (e.g., types).

"Extra-linguistic" mechanisms refers to "stuff" that isn't ordinarily part of a language, but you nevertheless need to be able to reason about programs. In this lab, we often work in contexts where the end result is some kind of statistical analysis. Those analyses are often only valid (in theory, if not in practice!) if certain assumptions about data generating process are true.

Now, statisticians have devised incredibly clever ways to make up for violations to these assumptions. In this lab, we don't strive to devise new corrections; instead, we try to understand existing problems via assumptions and corrections, and then design systems (such as programming languages, libraries, and frameworks) to either prevent the assumptions from being broken or make diagnosis easier. In that way, we use PL principles to push diagnostics earlier, making it so that we fail faster (a good thing because we don't waste resources!).

Because much of what we do involves deep dives into different data-driven domains, the PL principles that drive our approach aren't always immediately apparent. In the general case this is a good thing — we don't want to burden domain experts with a novel field when their goal is to just get something done! However, we do uncover interesting properties of programs in these domains that have implications for PL methods. This creates an exciting feedback loop between PL and the domains we work in.

First lab blog post! Read it to find out what MaPLE is about. :)